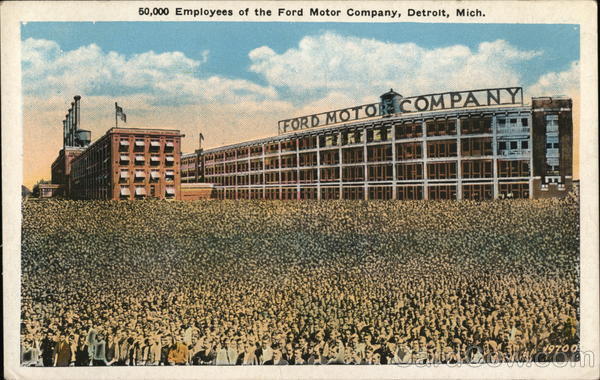

After the first industrial revolution initiated mass production with steam engines (Industry 1.0), the logic of mass production aimed at increasing worker productivity by breaking down tasks into small parts, as pursued by Henry Ford, brought about the second industrial revolution (Industry 2.0). The concept of Line Balancing emerged precisely from here.

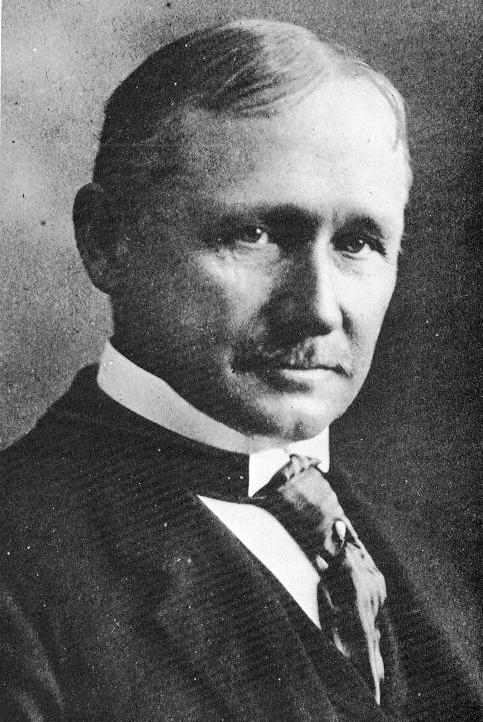

The principles of improving worker productivity, as elaborated with all the intricacies in Frederick Winslow Taylor’s book “The Principles of Scientific Management,” laid the foundation for Industrial Engineering and Lean Line Management.

By breaking down tasks into the simplest possible components and distributing them evenly among workers to minimize craftsmanship while maximizing production speed through repetitive tasks, this method was the starting point for Line Balancing and Industry 2.0.

Through these assembly lines, where Henry Ford shortened production times by over 80% in his famous factory in Detroit, the automobile ceased to be a commodity that only aristocrats could afford and became a dream for everyone. Thus, with the transformation of transportation and logistics, modern lives and cities began to emerge. This gave birth to what is known as Fordism, which became a subject in sociology books.

From Uniform Models to Diverse Products

One of the biggest handicaps in Ford’s factory was the provision of seriality in production through the production of single-color, single-type cars. This situation was a confirmation of Henry Ford’s famous saying, “You can have any color car you want from me, as long as it’s black.” Subsequently, with the entry of General Motors into the market, there came product-model-color diversity. With the 1930s, Europe also joined the game, and automobiles, including those from Ford, began to diversify and colorize by model and color.

However, Ford began to fall behind General Motors because, besides achieving simplicity by breaking down tasks into small parts, it could not fully develop its organizational skills.

Managing Product Diversity with Limited Resources

While these developments were happening in America and Europe, the Japanese had to produce differently from existing production methods. Beyond just making production serial, after World War II, they had to make good use of scarce Japanese resources (equipment, materials, etc.), produce automobiles on the limited land of Japan, and compete with Europe and America by creating competitive products.

For this, they needed different ways of ensuring product diversity. Developed by SMED technique, the company managed to reduce mold change times from 1 day to less than 10 minutes, increasing capacity and making it possible to produce different products on the same equipment.

Let Them Produce!

Another thing that the Japanese did differently from others was the “cultural distortions” in the production logic on assembly lines. Mass production had to be “mass” as the name suggests, and the assembly line should never stop. Even if there were quality errors, production had to continue, and these errors had to be corrected in the repair area afterwards, and production figures should be kept high at all costs.

But what is missed here and Taiichi Ohno‘s realization was an important detail. Even if there were quality defects, the “let them build it!” mentality led to a lot of rework waste and unpredictable repair costs. In increasingly complex automobiles, it was not possible for quality control to check every assembled part at the end of the line. Vehicles that were checked with limited points and corrected “relatively” if they had any defects or deficiencies posed a potential for potential quality problems in the eyes of the customer.

Quality In Place (During Production)

When Ohno examined the lines, he noticed that a mistake that could easily be rectified during assembly was postponed in order to continue assembly, resulting in longer repair times (and higher overtime rates) in the repair area. These repairs were purely firefighting, corrective activities that superficially solved the problem without getting to the root cause. This meant that the same quality defect was repeated over and over again, with the same repair times and hours of wasted time.

Therefore, the starting point of the concept we often talk about today, Quality In Place (or Built-In Quality), is the elimination of repair-rework wastes on classic assembly lines. This approach may initially be perceived as too much downtime on assembly lines; however, as problems are eliminated with their root causes, the foundation is laid for an assembly line that never stops due to the same problem again.

Who Knows the Job Best?

Another notable aspect of Toyota-style assembly lines is that the initial initiative regarding quality issues always belongs to the operator. Taylor and Ford’s designed assembly lines, operators were resources responsible for ensuring the operation of the lines with physical strength and were required to operate them continuously without stopping production. Therefore, because quality problems were “things” that needed to be solved later, operators never had a concern about solving problems or improving the line.

In the lines designed by Ohno, however, operators were the first individuals responsible for quality when faced with any quality problem, they had the authority to stop the line by pulling the Andon cord. They were not hired muscle just to keep production going, but rather employees responsible for quality and efficiency improvement with their ideas and suggestions. Because according to Ohno, “Quality is not controlled, it is built in!” The assembly lines where the perception of “The one who does the job best knows best” emerged form the origins of both the Toyota Way‘s fundamental value of “Respect for People” and Jidoka, one of the main pillars of the TPS.

Leadership and Line Management

Another significant aspect where Lean Assembly lines diverge from classic assembly lines is the concept of line leadership. Classic assembly lines were designed based on the principle of continuous operation, where workers were paced by a certain conveyor speed. Workers had to be filled with tasks in a way that would not allow them to think as much as possible, by repeating the same task as quickly and standardly as possible.

Ohno’s pioneered concept of Built-In Quality adopted the idea of detecting and eliminating quality errors while producing, therefore it also introduced the concept of a Line Leader responsible for intervening in encountered problems and overall “order” of the line. Line Leaders were in a position to lead units of 5-7 people on the assembly line, fully in charge of all tasks being performed, responsible for the performance and quality of the line, and providing support to team members on the line in case of absenteeism and performance fluctuations. In addition to requiring a strong problem-solving skill, these leaders were far beyond the muscle stacks expressed by

Considering that many factories still have teams of 50-80-100 people typically under a single shift supervisor, it’s not difficult to say that this method is part of a quite hierarchical and systematic structure. We will delve into the details of this structure later.

Continued in the Next Article

In this article, we covered the brief history of Assembly Lines and the concepts leading from Classic Assembly Lines to Lean Assembly Lines and Line Management. In the next article, we will continue with the basic principles of line balancing in an assembly line.

If you would like to learn more about this subject and learn line management and line balancing in practice here to register for the Yamazumi Training.

References

- Taylor, F. W., The Principles of Scientific Management, 1911

- Ohno, T., Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production, 1988

- Jones, D. T., Womack J., Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation, 1996

- Toyota Motor Corporation, The Toyota Way 2001, 2001